Are We Getting Poorer? The Harsh Reality of America’s Economic Gap

Finances. While this word may not affect some, it represents struggle for millions of Americans in poverty or below the poverty line. The reach of this is closer than many may think, affecting not just a scarce few but even the students sitting next to you in class.

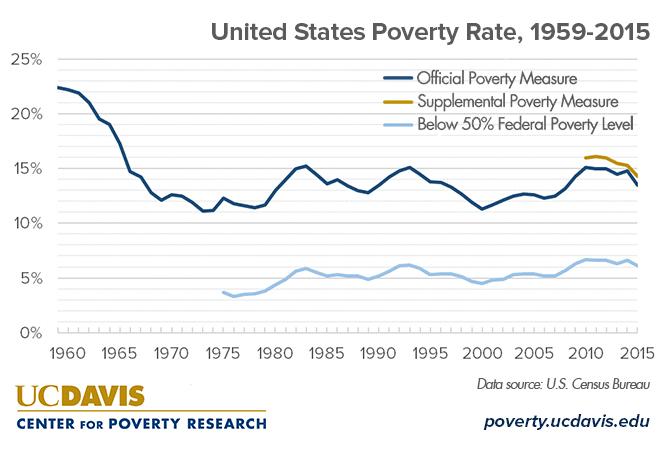

As it turns out, America’s rate of poverty is growing, day by day. The poverty rate in 2010 was 15%, which was a steep 12.5% incline from the rate in 2007. The poverty rate in 2015 was lower at 13.5%. This was the first time in five years that it decreased. Though the number seems small, that percentage covers 41.1 million Americans, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s official measure. (This census only reached households, however, meaning it does not include the impoverished who are homeless.)

According to the Pew Research Center, in a household with three people, being middle class means making between about $42,000 and $126,000. More is upper-class, and less lower-class. This means that the expectation for a family of four (average family size) is to make over $42,000 annually, which is not achievable for a growing number of families, including the families of some MMS students.

As the graphic (obtained from the University of California, Davis’ Center for Poverty Research) below illustrates, while the rates of poverty in the 1900’s were much higher than the 2000’s, the 2000’s has increased from a rate of 11.3% in 2000 to 13.5% today, (and an especially high spike of 15% in 2010) while the supplemental poverty measure indicates an even higher rate than the official in recent years. The steep decline from the rate in the 1900’s was due to launch of major War on Poverty programs, meaning the rate now fluctuates from 11 to 15%. However, the light blue line indicating households below the 50% federal poverty level has increased in the past decade.

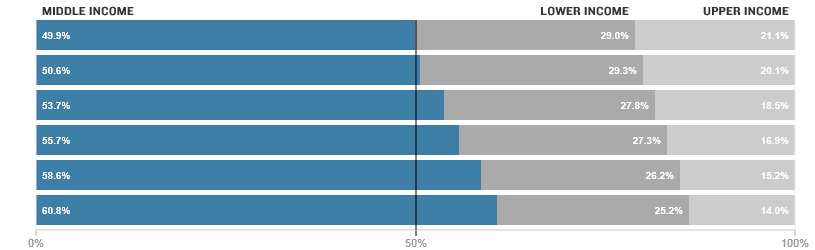

It also happens that the amount of Americans in the middle class are decreasing, according to studies by Pew Research Center. A 2015 analysis of government data shows that middle class is continuing to shrink, with 120.8 million adults in middle class and 121.3 million living in either upper or lower class households. This is due to factory closings and other economic factors that make financially succeeding more difficult.

“The hollowing of the middle has proceeded steadily for the past four decades,” Pew concluded. But not only is the amount of middle class households in the population going down, but so is their income. The research center found that the middle classes’ median income is down four percent from 2000. The bar graph below shows that not only has the percent of the population that is in the middle class dipped below fifty percent, but the percentage of those in the lower class has increased, along with those in the upper class.

In the graph below, the years, vertically from bottom to top, show data for 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001, 2011, and 2015.

And with the decline of middle class and increase in lower class comes some adverse effects, one of them being teen’s mental health. A teen’s mental health becomes worse the poorer they get, according to Drew McWilliams, a clinician and the Chief Operating Officer at Morrison Child and Family Services in Portland, Oregon. Since the financial collapse in 2008, he says he has seen a constant increase of children suffering anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “Parents are struggling with their own issues and that spills over to their kids,” he said.

The developing brain is also more vulnerable to stress, says Huffington Post. Research has begun to show how the constant barrage of stress hormones can change the way the brain develops, causing behavioral and psychological disorders and putting children at risk for mental illness later in life. An APA survey also revealed that money remains a top stressor, and the child advocacy group First Focus reported that the foreclosure crisis had affected eight million children, of which 2.3 million had lost their homes. In 2011, researchers studied the brains of 317 students and found that students with a lower socioeconomic status tended to have a smaller hippocampus, unlike their affluent counterparts. A smaller hippocampus has been linked to several psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, anti-social personality disorder, major depression and PTSD.

To further research the impact of financial struggle on teens, MMS students were interviewed anonymously about their tough financial conditions.

The first student interviewed is not on welfare, but her mother is unemployed because she goes to school and is unable to work. She says her conditions of living are affected by this because, “You can’t necessarily get all the things you want anymore. You can’t do things that require money.” She says that single parenting makes finances difficult, and her family has had to make compromises to make ends meet: “We don’t eat out as much as we used to. We were only allowed to get a few gifts for Christmas, and for my birthday I’ll only be allowed to get a small gift.” She goes out every three months when her mother receives money, but spending is limited to under $30. She’s also been forced to move because rent was too high. She thinks it is important for teens to have a better understanding of the poor; she says, “I’ve seen people get picked on because of their financial status, and it annoys me because you don’t know what people are going through.”

For another student interviewed, she believes race and divorce have all played a part in her family’s financial difficulty. Her parents both work multiple jobs. She’s had to live with her grandmother and limit her meals to basics–mostly Ramen noodles–to help make ends meet. She shares one bathroom with a family of six. Not many people know about her struggles: “I guess family [knows]. It’s not something we just tell anyone.” She doesn’t go out for fun often, and while she wishes people knew more about the poor, she thinks “that wouldn’t change anything.” Moving is common for her because of finances: “My family has moved constantly in the past because of work, but mostly because of issues with leases.”

The third student interviewed has switched on and off of welfare in the past, and her parents work multiple jobs. She says immigration has played a part in her family’s financial problems: “Immigration and Visas make it hard to get employed because sometimes employers don’t want to deal with the complications of some Visas, and there’s going to be judgement because of your accent.” She says very few know about her status–only very close friends and family. She rarely goes out for fun, adding, “You can’t do things that aren’t necessary when you can barely afford what is.” She, like the other two students interviewed, reported having to move frequently because of her parents’ work: “The jobs we take normally last one to three years; after that it’s a big job hunt and eventually onto the new place.” She wants people to be more informed about the poor, explaining, “People tend to generalize people based on their financial struggles in so many ways: from intelligence to race to hard work. I’ve heard stories of people yelling at parents who are on welfare that they are bums sucking up tax money… that they don’t work hard and can’t do anything. That’s a huge stereotype and incredibly untrue, which makes it so frustrating to hear. You can be smart and hard working and still struggle. It’s difficult to have people not understand why you can’t go out to that ice cream shop or the mall…always having to find an excuse to not go or just saying you can’t afford that, or that, or that either. It’s always awkward and frustrating, and sometimes people are really insensitive. You constantly feel misunderstood.”

The U.S. Census Bureau releases the poverty rate every September in relation to the prior year, meaning the rate for 2016 won’t be out until September 2017. For now, recent figures indicate that well-over 43 million Americans live in poverty, and about 15 million of them are children (NCCP). Research shows, though, that typical families need an income of about double the established poverty level to cover basic expenses. Using this standard, 43% of children live in low-income families: nearly half of American children and teens. Thus, the chance that someone you interact with daily is dealing with the stress of their family’s financial troubles is likely. The chance that someone you know is silently struggling with unemployment, hunger, or housing issues is probable. The likelihood that a classmate is burdened by the weight of America’s growing poverty rate is considerable. Information and compassion can go a long way.