Valentine’s Day has long been criticized for various reasons. A Time article once reported, “complaints about Valentine’s Day have been going strong since at least 1847.” As for the complaints in question? Accusations have been thrown: of its enforcing of traditional gender roles and relationship structures, of the shame and burden it thrusts on those without a relationship, and, of course, of the commercialization that has come with the holiday. Even the Wildcat Voice has published an article on the topic, dubbing the celebration, “The Most Pointless of All Holidays.”

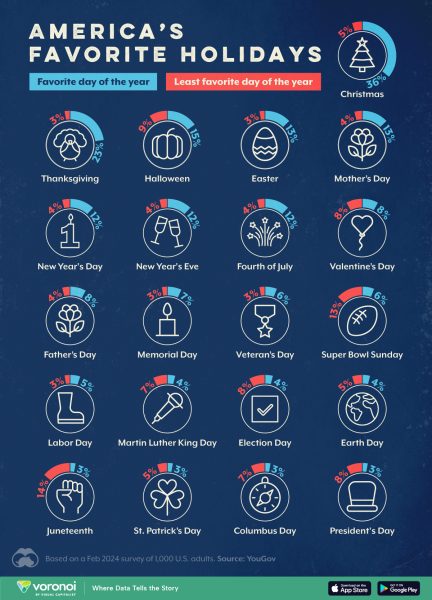

A YouGov survey given to 1,000 Americans would have 8% of it’s participants choosing Valentine’s as their least favorite day of the year—although, in sharp contrast, 8% also chose it as their favorite.

Teacher Mrs. Saunders says that she does not celebrate Valentine’s Day at all with her husband of twenty years. “I feel it’s silly.” She elaborated that when it comes to going out to dinner, it’s far easier to secure babysitters and reservations on a different day. “It doesn’t mean anything when someone expresses their love on Valentine’s Day. It means more on a random day because then it’s sincere.”

Eight-grade student Javia Smith would comment that she dislikes the holiday. “I feel bad for people who don’t have anybody.” Such criticisms are common—that the day pressures those in relationships, while alienating those who aren’t.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay would publish an opinion article on the Nation in 2012 extensively criticizing the day. “The RIC makes people unhappy by pressuring them to spend lots of money and at the same time making it impossible for all but a small percentage to fulfill their ‘duty.’ The remainder of folks, on the other hand, are unable to participate or are left with feelings of inadequacy. Whether people are coupled and can’t afford the trappings of romance or are single and focusing their emotional energy on friends, the RIC has nothing for them.” Explaining the holiday’s role in perpetrating traditional ideas of romance and gender, its alienating nature, and the commercialization involved in it all, she would end the essay with a call to action— “Above all, let’s find a way to honor ourselves that does not rely on buying stuff.”

One of the negative comments people can give for the day is more prominent than others. Criticisms of commercialization regarding Valentine’s have always been at the forefront. An article from 1847 run in the New York Daily Tribune would say, “We hate this modern degeneracy, this miscellaneous and business fashion. Send a Valentine by the penny post too? Bah! Give us the sweet old days when there was a mystery about it.”

A great amount of money is spent on the holiday, with numbers rising every year—2025 set record-breaking numbers, with the National Retail Federation predicting $27.5 billion to be spent on the day. The day has become synonymous with the communication of love with money, of the conflation of romance with products. Jewelry, cards, flowers, chocolates—for the more pure romantics (or the more bitter cynicists), these things represent a corruption of real romance by capitalism—or the unfeeling arm of corporate commercialization, which reduces everything to a version of itself which can produce with the greatest speed.

The monetization of the holiday becomes evident every time February 14th comes around, with a barrage of hearts and pink put on by every store and corporation. Even those opposed to Valentine’s can find a way to spend money: a 2015 article run by the Washington Post would tell the story of a restaurant that sold an “Anti-Valentine’s” menu, or a website called “Ban Valentine’s Day”, which would sell hoodies “promoting the cause.” Even the hate of the holiday has become monetizable—interesting, isn’t it?

Some have taken to celebrating something different for February—cue Galentine’s Day, a holiday originating in the 2009 sitcom “Parks and Recreation.” Rather than romance, those participating in Galentine’s Day celebrate each other; it’s a full day of female friendships, delighting in sisterhood, and so on. But it’s not as if this holiday is free from the problems that plague its more romantic equivalent. Micheal Schur, the creator of Parks and Recreation, commented on the holiday, saying, “It’s sort of impossible in America for anything to enter the culture and then not be commodified, you know? … Anytime anything you write sort of penetrates this disparate culture that we’re in and catches on and sort of is echoed back to you, that’s delightful, but it also was odd to see it sort of warped a little bit and converted into this thing that’s being used by brands and websites and corporations in order to have a sale on whatever it is they’re hawking. Because obviously, that wasn’t the point of it.”

Nancy Coleman would write an article in the New York Times on companies “cashing in” on the holiday, reporting several things—Hallmark taking upon Galentine’s cards, or Party City selling Galentine’s balloons along with Valentine’s. As Coleman wrote, “Bars, coffee shops, boutiques and fitness studios are also hosting their own Galentine’s promotions and events.” If anything can be gleaned from it all, it is that even the rejection of romance for friendship has become marketable.

The holiday was not always celebrated as it is today—this is a given, for all holidays change drastically with time. Valentine’s origins are contested, with several theories existing, with the only thorough line between them being the blatant un-romanticism of it all. One theory runs that it was an ancient Roman love-making fest. An article in the New York Times would describe the original festival as a “raucous, wine-fueled fertility fest.”

Another theory previously appeared in the Wildcat Voice, suggesting that the holiday was a celebration of the execution of Saint Valentine. A English professor at the University of Kansas, Jack B. Oruch, dedicated himself to a theory that Valentine’s had originated from the poems of Geoffrey Chaucer, who wished to bring popularity to his saint through connecting him with romance. The origins of Valentine’s, while contested, do seem to have one thing in common—their disconnection from the Valentine’s we celebrate today.

But despite what this article is about, there are ultimately just as many people who picked Valentine’s as their favorite holiday as those who picked it as their least. That such commercialism is not unique to Valentine’s, that there is merit to “extravagant displays of affection” (Elizabeth Flock), that a day spent with loved ones is pleasant regardless of other troubles. An anonymous student would tell the Wildcat Voice in 2019 that, “I think Valentine’s day is cool, because you can buy chocolate for very cheap. I don’t understand why people get so angry over it. Like, I’m sorry that you’re lonely.”

If there is any criticism of Valentine’s Day that holds merit, it is the over-commercialization of the holiday. But I think it is unnecessary to view February 14th as a problem in itself. The issues taken with the holiday never seem unique to it—see how Galentine’s Day was commercialized just as quickly. How different is the cheap bombardment of pink and hearts on every product sellable to the plastering of snowmen and Santa when the holidays roll around? The commodification of romance is not any more different than the commodification of patriotism, of thankfulness, of some vague concept of holiday and family. That every emotional part of every celebration be sanded down to its most marketable version is commonplace by now. Here is such a concept: Valentine’s is not the malady—merely a symptom of something greater.

Valentine’s is a holiday people seem to love and hate in equal part—what do you think?